Mirjam Neelen & Paul A. Kirschner

Last month, the Online Learning Consortium published an international report titled Neuromyths and Evidence-Based practice in Higher Education (thanks to Donald Clark for pointing it out on Twitter).

The reason for this research is articulated well by Professor Howard-Jones in the Preface. He says:

Educators make countless decisions about their teaching and course design that are likely to impact on how well their students learn. At the heart of these decisions is a set of ideas about how learning proceeds, so it is self-evidently important that these ideas are valid and reflect our current scientific understanding. And yet, a growing body of research is revealing that many of the underlying beliefs of educators about learning are based on myth and misunderstanding – particularly in regard to the brain… With our increasing concern for the student learning experience, and our growing awareness of the dangers of online misinformation, the need for university and college institutions to ensure their practice is scientifically grounded and evidence-based[1] has never been greater.

The research

The researchers sent out an online survey with three sections:

- Neuromyths[2] and general knowledge about the brain

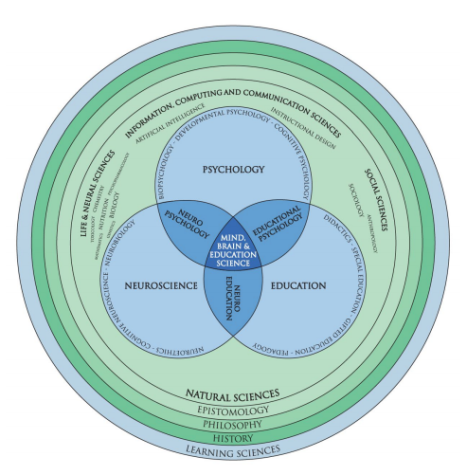

- Evidence-informed practices from the learning sciences and Mind, Brain, and Education (MBE) science related to the brain, teaching practices, and learning processes.

- Professional development and collected demographic data (not discussed in this blog)

This report is relevant reading for all learning professionals as it provides an opportunity to reflect on our profession overall, on our own individual level of knowledge, and on how we approach professional development.

The survey was sent by email to the Online Learning Consortium (OLC) listserv, which included 65,780 email addresses across higher education institutions worldwide. The overall results are informed on 929 completed surveys[3] (those were the ones who were completed and met the researchers’ inclusion criteria). Respondents included full-time and part-time instructors, instructional designers, professional development administrators and ‘other’ (see breakdown below).

Although respondents indicated that they were interested in learning more about the brain and its influence on learning and also stated that they found scientific knowledge about the brain valuable to teaching practice, course development, and professional development, the results were a bit disappointing.

The results on the neuromyths survey showed that the median correct responses were 68, 66, and 65% for instructional designers, instructors, and administrators respectively. This means that a) the researchers took the median[4] from the correctly answered statements for each group and then b) determined if there were significant differences between the three groups.

Neuromyths survey results (median % correct responses shown on y-axis)

Interestingly, there was a significant difference between those respondents who read and did not read journals related to neuroscience, MBE science, and psychology (hint, hint, what does this tell you?).

Difference between correct responses on neuroscience statements for those who read neuroscience, MBE, or psychology related journals compared to those who don’t (median percent correct responses shown on y-axis) Difference between correct responses on neuroscience statements for those who read neuroscience, MBE, or psychology related journals compared to those who don’t (median percent correct responses shown on y-axis) |

Difference between correct responses on evidence-based practice statements for those who read neuroscience, MBE, or psychology related journals compared to those who don’t (median percent correct responses shown on y-axis) Difference between correct responses on evidence-based practice statements for those who read neuroscience, MBE, or psychology related journals compared to those who don’t (median percent correct responses shown on y-axis) |

The results for the evidence-informed practice survey show that instructional designers (median = 83%) have a significant greater awareness of evidence-informed practices than administrators (median = 80%) and instructors (median = 79%).

Evidence-based practice survey results (median % correct responses shown on y-axis)

For both topics (neuromyths and evidence-informed practice), the Online Learning Consortium research results clearly show that people who read journals related to neuroscience, psychology, and MBE science have greater awareness of neuromyths, general information about the brain, and evidence-informed practice. They also reveal a positive relationship between people’s knowledge of neuroscience, psychology, and MBE science and the professional development types (e.g., professional training, workshops, MOOCs related to either neuroscience, psychology, or MBE science) they have engaged with. In other words, when people educate themselves in a certain domain, they have more knowledge in that domain. No surprise, right?

Of course, the report itself provides more details, but we think that these two are the most useful for learning professionals to reflect on.

Your turn

We have reproduced the survey questions below (first two sections only) so that you, as learning professional, can assess how solid or weak the foundation is that you stand on as a practitioner. We provide the answers in a footnote. You can print out the tables and select your answers, or just jot down the number with Correct or Incorrect (or however you want to do it).

| Neuromyths and general statements about the brain [see neuromyths answers below] | Correct | Incorrect | |

| 1 | Listening to classical music increases reasoning ability. | ||

| 2 | A primary indicator of dyslexia is seeing letters backwards. | ||

| 3 | Individuals learn better when they receive information in their preferred learning styles (e.g., auditory, visual, kinesthetic) | ||

| 4 | On average, males have bigger brains than females. | ||

| 5 | Some of us are “left-brained” and some are “right-brained” due to hemispheric dominance and this helps explain differences in how we learn. | ||

| 6 | We only use 10% of our brain. | ||

| 7 | Normal development of the human brain involves the birth and death of brain cells. | ||

| 8 | It is best for children to learn their native language before a second language is learned. | ||

| 9 | The brains of males and females develop at different rates. | ||

| 10 | Learning is due to modifications in the brain. | ||

| 11 | Learning is due to the addition of new cells to the brain. | ||

| 12 | There are critical periods in human development after which certain skills can no longer be learned. | ||

| 13 | Learning occurs through changes to the connections between brain cells. | ||

| 14 | Information is stored in networks of cells distributed throughout the brain. | ||

| 15 | Extended rehearsal of some mental processes can change the shape and structure of some parts of the brain. | ||

| 16 | The left and right hemispheres of the brain work together. | ||

| 17 | When a brain region is damaged, other parts of the brain can sometimes take up its function. | ||

| 18 | Brain development has finished by the time children reach puberty. | ||

| 19 | Learning problems associated with developmental differences in brain function cannot be improved by education. | ||

| 20 | Individual learners show preferences for the mode in which they receive information (e.g., visual, auditory, kinesthetic). | ||

| 21 | Production of new connections in the brain can continue into old age. | ||

| 22 | We use our brain 24 hours a day. | ||

| 23 | Mental capacity is genetic and cannot be changed by experiences. |

[neuromyth answers] 1 = Incorrect, 2 = Incorrect, 3 = Incorrect, 4 = Correct, 5 = Incorrect, 6 = Incorrect, 7 = Correct, 8 = Incorrect, 9 = Correct, 10 = Correct, 11 = Incorrect, 12 = Incorrect, 13 = Correct, 14 = Correct, 15 = Correct, 16 = Correct, 17 = Correct, 18 = Incorrect, 19 = Incorrect, 20 = Correct, 21 = Correct, 22 = Correct, 23 = Incorrect

[evidence-based answers] 1 = Incorrect, 2 = Incorrect, 3 = Incorrect, 4 = Correct, 5 = Correct, 6 = Incorrect, 7 = Incorrect, 8 = Correct, 9 = Incorrect, 10 = Correct, 11 = Correct, 12 = Incorrect, 13 = Correct, 14 = Correct, 15 = Correct, 16 = Incorrect, 17 = Correct, 18 = Correct, 19 = Incorrect, 20 = Correct, 21 = Correct, 22 = Correct, 23 = Correct, 24 = Correct, 25 = Correct, 26 = Correct, 27 = Correct, 28 = Correct

What to do?

As learning professionals, we hopefully all agree that professional development (development of knowledge and practice enhancement in various shapes and forms) is critical for providing value to our clients and learners in general.

However, apparently, we’re not doing that great. The study reveals that “instructors, instructional designers, and administrators can be susceptible to believing neuromyths and may not be fully aware of evidence-informed practices from the learning sciences and MBE science”(p. 37). At the same time, the study shows that professionals in higher ed have a high level of interest to learn more about the brain and its influence on learning.

We think it’s fair to say that both results reflect the overall state of our profession.

The question is: What’s going on? Why do we say that we want to know more about what the learning sciences tells us about learning and why don’t we invest enough in building our knowledge in that space? There’s obviously work to be done!

The report recommends the following three things which we have translated from a focus on higher education to the overall learning profession:

- Professional bodies in learning and instruction need to assess the awareness of neuromyths, general information about the brain, and evidence-informed practices among their practitioners (learning professionals).

- Learning professionals should engage in self-directed learning, such as reading journals in their fields, the learning sciences, and MBE science. Professional bodies and organizations can support this by sharing open access resources.

- Professional bodies in learning and instruction need to examine the alignment and integration of current professional development opportunities with the learning sciences and MBE science.

So, what are we doing or going to do to improve our profession and what are you doing to improve your practice? Here are a few resources to get you started:

- Designing learning experiences in an evidence-informed way

- Brain-based bullocks

- What makes a top teacher?

- No feedback, no learning

References

Betts, K., Miller, M., Tokuhama-Espinosa, T., Shewokis, P., Anderson, A., Borja, C., Galoyan, T., … Dekker, S. (2019). International report: Neuromyths and evidence-based practices in higher education. Online Learning Consortium: Newburyport, MA. Retrieved from: https://olc-wordpress-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/2019/10/Neuromyths-Betts-et-al.-September-2019.pdf

[1] The authors of the report use this term. As you know from reading our work, we prefer to use the term evidence-informed.

[2] Misconceptions that arise from misunderstanding, misquoting, misinterpretations, or the misreading of information about the brain.

[3] Two things need to be noted. First, there might be a self-selection bias at work here. Self-selection bias results when survey respondents are allowed to decide entirely for themselves whether or not they want to participate in a survey. This can lead to biased data, as the respondents who choose to participate may not represent the entire target population. Second, 929 out of 65,780 is just a small percentage of the total population (1.4%).

[4] The median refers to the value that separates the higher half from the lower half of the data set, or the middle value in a ranked order sequence. For example, when the data set shows results 1, 3, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9, then ‘6’ is the median; there are three values higher than 6 and three lower. In the context of this study, the median is a good measure because some statements had a very low ‘correct’ score (e.g., 15%) and some had a very high ‘correct’ score (e.g., 93%). By taking the medians, these ‘outliers’ are avoided, and the median shows a better measure of ‘central tendency’.

Reblogged this on From experience to meaning….

LikeLike

Reblogged this on kadir kozan.

LikeLike