Mirjam Neelen & Paul A. Kirschner

On February 1, Mirjam and Patti Shank presented at the Learning Technologies Conference in the UK on how we, as learning professionals, should help people and organisations adapt to the ever-changing world (here’s the link to their talk). They focused on global changes and on the impact of those changes on the work world. For example, organisations are dealing with quickly changing business needs and priorities, new and constantly evolving worker skills, and the need for workers to be able to execute complex skills. It’s the last that seems to cause confusion. Complex skills seem to be hard for many to ‘grasp’. This is clear when we look at general practice in corporate learning design, where complex skills are often decomposed (broken up) into separate constituent skills and both learned and practiced as if they don’t have to be applied on the job in an integrated manner. Perhaps you’re raising your eyebrows by now. “WTF?”, you might think.

To make this clear, first we’ll paint a (simple) picture of the world we currently live in and discuss what that means for our working life. Then we’ll discuss what complex skills are and how we should design for them to support learning transfer (so as to ensure that people can apply what they learn on the job) in the workplace.

Today’s world and work

We think that we all agree that the world is rapidly changing trough advances in computers, software, data analytics, and machine learning. This means that automation in the past meant that routine, cognitive and physical tasks were taken over by machines, now it’s becoming the case that fewer people will be needed for jobs with non-routine, physical and cognitive tasks (as technology will be able to take over tasks these quadrants as well). This makes the changes in the 21st century quite different from the those in the 20th. The image below (Frey & Osborne, 2013) shows some examples of jobs in the 4 quadrants.

Frey and Osborne’s Quadrants

So, the question of course is: What does that mean for us as workers? The answer is “We’re not really sure”. However, it’s likely that the cognitive tasks that still must be completed by humans will become increasingly complex and because of the accelerated changes, these cognitively complex task-focused skills need to be accompanied with skills such as problem-solving, critical thinking, and decision-making. These task-based skills in combination with the higher order thinking skills is where complex skills come in.

What are complex skills?

When we talk about complex skills, it might help to think about the idea that ‘the whole is more than the sum of its parts’. Complex skills are skills that consist of many elements that interact with one another. Again, WTF? Think of it this way…Playing a scale on the piano has a certain number of elements (notes), but there is no interaction between them. The order, tempo, timbre, etc. is the same in both directions and, thus, it’s not really complex. Playing a nocturne by Chopin may have the same number of elements (notes) or fewer, but the interaction between the elements is great, and thus this is much more complex.

Ascending and Descending Chromatic Scale

Let’s say we’ve identified a performance discrepancy in the workplace and we’ve determined a performance objective. When dealing with cognitive complex skills, they can be decomposed into more specific “constituent skills and the interrelationships between them” (Van Merriënboer & Kirschner, 2018, p. 85). The image below shows some examples of the relationship between skills in the context of driving a car.

The skills lower in the hierarchy enable the learning and performance of the skills higher in the hierarchy (a prerequisite relationship, for example you need to be able to properly use the steering wheel before you’re able to navigate a bend) while the skills at the same (horizontal) level in the hierarchy can be specified as temporal (one skill takes place before the other, e.g., starting the engine before you drive off), simultaneous (skills that might be performed at the same time, e.g., when driving you’re using the gas pedal and steering wheel at the same time), or transposable (skills can be performed in any desired order, e.g., when you park the car, you can switch off the engine and then pull up the handbrake, or the other way around[1]).

In the context of learning, all of this is critical because as a learner, you need to learn the main ‘complex skill’ in an integrated manner! So, when we’re dealing with complex skills, we’re dealing with complex learning. Complex learning “involves integrating knowledge, skills, and attitudes; coordinating qualitatively different constituent skills, and usually transferring what’s learned … in training settings to … work settings” (Van Merriënboer & Kirschner, 2018, p 2).

Interestingly, most learning professionals will agree that an authentic job task is best for workers to enable them to integrate the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary for effective learning transfer and task performance. However, what many don’t realise is the consequences that this has for instruction and learning design. Let’s look at the example below from Van Merriënboer & Kirschner, (2018) to illustrate the point.

Complex skills as part of an authentic job task

The image shows a hierarchy of constituent skills for the moderately complex skill ‘searching for relevant literature’.

https://loft.io/guide/eeole/goals/, based on Van Merriënboer & Kirschner, (2007)

What you can clearly see in the hierarchy, is the relationship between the various skills. The major point here, is that the learner should NOT learn skill 1 (Select an appropriate database), skill 2 (formulating a search query), and so forth independently as this leads to fragmentation (the tendency to analyse a complex learning task in small pieces corresponding to specific learning objectives, and then teach them piece-by-piece without paying attention to the relationships between pieces which hinders complex learning and competence development.). The main skill ‘searching for relevant literature’ needs to be learned in an integrated manner instead; as a whole task. In this case that means, for example, that the learner starts with performing relatively simple yet authentic literature searches, that incrementally become more complex (more elements and more interaction between the elements).

Another important point is that the image also shows the associated knowledge and attitude for each skill. So, for example, in order to select the best database for the search query, the learner needs to have knowledge on various databases and their characteristics. ‘Translating clients research question into relevant search terms’ requires a client-centred approach to make sure that you really understand what the client is looking for and in what context.

What could an effective approach to this performance discrepancy look like, assuming that the Learning Designer and the subject matter experts have agreed that the skills hierarchy as it stands is correct?

How to design for complex skills

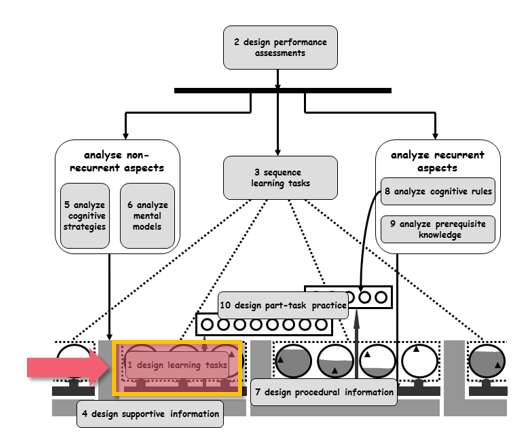

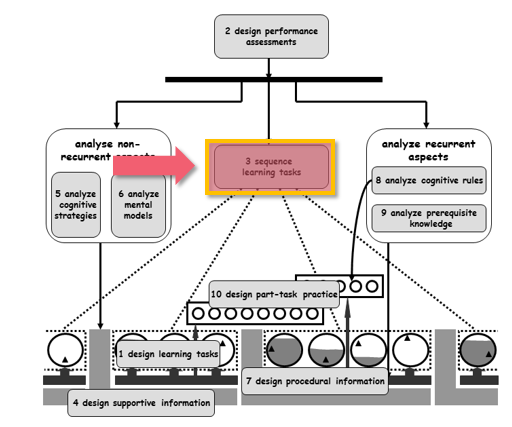

A first critical step is to design learning tasks, based on the skills hierarchy. As Van Merriënboer and Kirschner (2018) word it: “It is the pebble that is cast in the pond[2]” (p. 53). The tasks clarify what the learner will be required to do during and after the learning experience.

The learning tasks are based on real life tasks, which usually means they’re ill-structured, multidisciplinary, and sometimes might be team tasks instead of individual tasks. They should be organised in simple (yet authentic!)-to-complex categories or task classes (see sequence learning tasks in the figure below).

Ideally, even the first task classes (the simplest versions of the whole-task ‘searching for relevant literature’, should consist of authentic whole tasks that professionals actually encounter on the job. For example, the learner needs to carry out searches based on an unambiguous question in a clearly defined domain with straightforward search terms and few relevant databases, and so forth. The task classes become increasingly complex (ambiguous question, multidisciplinary combination of domains, many interrelated search terms via complex Booleans,…) as the learner progresses. What’s critical to note is that each new task class contains learning tasks in the learner’s zone of proximal development (Vygotsky, 1978).

Learning tasks at each ‘complexity’ level should provide the right level of guidance and support to the learner which fades within the task class until the final tasks are without support and guidance (and thus assess whether the learner has mastered what needed to be mastered). To understand what type of guidance and support you need to design, you need to create a fully worked-out example of the task, including acceptable solutions for the problem and the required problem-solving process.

For this blog, it would be too detailed to explain this extensively (Van Merriënboer and Kirschner wrote a whole book on this! A good begin is the chapter here), but we’ll give one example for supportive information (see figure below) in the context of ‘searching for relevant literature’. The reason why we focus on supportive information is because complex learning primarily deals with non-recurrent[3] task aspects, which are ill-structured (e.g., there’s not one optimal solution). In the case of ‘searching for literature’, one example is the fact that a) a client comes with a, not necessarily well-defined, research question and b) there’s not one ‘best’ way of running the search queries.

Supportive information helps bridge the gap between newly presented information and what they already know. An example of supportive information in this case is a modelling example to illustrate a Systematic Approach to Problem-Solving (SAP). Learners could investigate how an experienced librarian constructs search queries (including situations in which something went wrong). The example would make visible and explicit what the librarian was thinking and why (s)he made certain decisions or changes along the way.

Is all of easy, you might ask? Well, no. But we all know learning can be hard, so that’s no excuse. Is it worth it? Yes! Of course, our examples are only the very beginning. For a detailed explanation, we recommend reading Ten Steps to Complex Learning (Van Merriënboer & Kirschner, 2018) and even better, read it with your team members so that you can get the conversation going on how to design effective learning approaches for the complex skills that we’re dealing with in today’s workplace all the time!

References

Frey, C. B., & Osborne, M. A. (2013). The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation? Oxford, UK: Oxford Martin School. Available at http://acikistihbarat.com/Dosyalar/effect-of-computerisation-on-employment-report-acikistihbarat.pdf

Merrill, M. D. (2002). A pebble-in-the-pond model for instructional design. Performance Improvement, 41(7), 39-44. Retrieved from http://mdavidmerrill.com/Papers/Pebble_in_the_Pond.pdf

Van Merriënboer, J. J., & Kirschner, P. A. (2018). Ten steps to complex learning: A systematic approach to four-component instructional design. London, UK: Routledge.

Van Merriënboer, J. J., Kirschner, P. A., & Kester, L. (2003). Taking the load off a learner’s mind: Instructional design for complex learning. Educational psychologist, 38(1), 5-13. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/27699619_Taking_the_Load_Off_a_Learner’s_Mind_Instructional_Design_for_Complex_Learning

Vytotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, M.A.: Harvard University Press.

[1] Examples from Van Merriënboer & Kirschner, 2018

[2] A Pebble in the Pond is a practical and content-oriented approach to instructional design which starts by specifying what the learners will do, that is, the design of learning tasks (i.e., the pebble). This one pebble starts all of the other activities rolling. The term was introduced by M. David Merrill.

[3] An aspect of complex task performance for which the desired exit behaviour varies from task to task / problem situation to problem situation (i.e., it involves problem solving, reasoning, or decision making). This is in opposition to recurrent which is an aspect of complex task performance for which the desired exit behaviour is highly similar from task to task / problem situation to problem situation (i.e., a routine).

Reblogged this on kadir kozan.

LikeLike