Mirjam Neelen

This blog is about Patti Shank’s 2nd book in the ‘Make It Learnable’ series. Although I must admit I do like Patti as a person and admire her work, those aren’t the reasons why I’ve decided to write a review of her newest book. As I recently explained in two of my blogs (here and here), I’m an advocate for having nuanced conversations around improving L&D practice and for a professional approach to designing learning experiences (based on learning sciences, that is!). Shank ticks both boxes and I simply believe that her research and how she has captured it in her book are critical for our field. Last but not least, the way she has written it all up makes it understandable and applicable for those of us who design learning experiences.

Her book is about practice and feedback and there are many reasons why this is important, the main one being that meaningful practice and feedback are generally NOT part of learning within organisations and that’s a serious problem. As learning professionals, we’re trying to help solve business problems and therefore must think about what people need to be able to do to overcome challenges and to achieve desired outcomes. Consequently, giving them a lots of information (content dump) simply doesn’t cut it. It doesn’t help people to learn, apply, and remember, and, so says Shank, these are the “three critical keys to supporting today’s work challenges” (p 3). In other words, we need to focus on transfer to the job (also see my blog here in which I discuss Salas et al’s research and explain why training shouldn’t be perceived as being an event) and that automatically implies that we need to provide realistic opportunities in real, complex, and messy work environments to improve knowledge and skills.

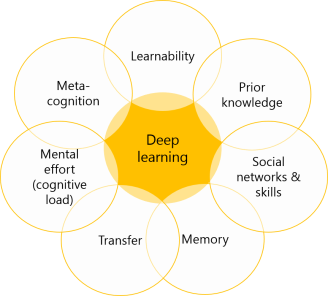

In line with this, we need to realise that the work that people do isn’t just a sequence of tasks. It’s more likely about complex mental tasks and a frequent need for updating skills. As jobs are becoming less routine and more complex, a focus on deep learning is critical. Deep learning means to learn for long-term use, or, for application. Shank lists the learning tasks that are required to achieve deep learning:

- Effortful understanding

- Relating content to already known information

- Finding underlying patterns and principles

- Applying learning to personally important problems

- Critically examining logic

- Coming to conclusions

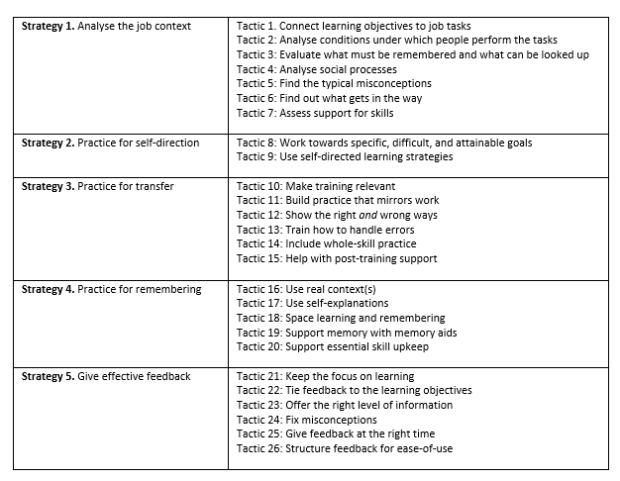

To put it simply, as learning professionals we need to concentrate on deep learning approaches, meaning that we should use relevant and meaningful learning tasks and strategies. It all sounds so obvious, doesn’t it? Sadly, we all know that this approach is rarely taken in response to employee learning and performance needs. Shank’s book offers us a ton of strategies and tactics (well, a ton is a bit of an exaggeration, there are 5 strategies and 26 tactics to be precise) to make it happen, so there’s some good news!

Shank has identified seven areas of research that give us insight into practice and feedback-needs to support deep learning:

She briefly but clearly discusses the science behind each one as well as how they relate to deep learning. This helps us understand the why so that later, when she discusses the tactics (the how), we, the reader, can get our heads around on why we should do what’s recommended. In other words, the book is itself structured to support deep learning (although of course it’s only the first step as next needed to apply it (practice the tactics and ask your team members for feedback!)).

Another reason for Shank to focus on practice and feedback in one book is because they go hand in hand. They belong together. As Shank writes in her book … “like fish and chips, Batman and Robin, peanut butter and bananas…” (p 35). I must admit that the last one doesn’t even sound attractive to me but hey, Patti Shank has always based her work on evidence so it must come from some reliable source…. (she says it’s coming from Elvis Presley 😊).

When you practice something, you apply what you’ve learned and feedback tells you what you need to change to get better or where you need to persist because you’re doing great.

Before Shank dives into the strategies, she explains practice and feedback in more detail, which again, sets the scene for the remaining sections that hold the more practical and applicable stuff. There are a couple of things from this chapter that I’d like to highlight as I think you should be aware of them at all times when you’re designing learning experiences. And even if you know them already, these principles are just so… key that there’s no harm repeating them.

Main principles of practice and feedback

The first principle is the relationship between performance objectives, learning objectives, and practice and feedback. The desired performance directs the learning objectives and next, learning objectives target needed practice and guide the evaluation of the practice (feedback). The image shows how this works:

What’s important in organisations, is that employees become ‘independently productive’ (as in performing tasks without assistance and without errors and what this looks like of course depends on the specific task for the specific job role) as soon as possible. Shank states that the main difference between inadequate performers and independently productive performance is the right type and amount of practice (this is the second main principle). People need a lot of practice to become proficient in something. One can wonder if (even the right type of) practice always makes perfect. There are many factors coming into play when it comes to competence (personality, motivation, temperament, general ability, and so forth) so it’s not necessarily that practicing the right way at the right time will always make you proficient in that area. But if you want or need it as a learner, it’s your best bet.

Adequate practice, first, has specific goals (this is where the job context is critical as this will tell us the level of skill employees should have and then we need to figure out how much practice they will need to get to that level and how they’ll maintain those skills). Next, it matches the challenge level to both current skill level and prior knowledge and this is where the difference between novice learners and expert performers comes in. Effective practice offers the right kinds of practice (for example, for a novice learner you would explain basic concepts first before they would start practicing and you need to provide way more scaffolding and guidance compared to experts[1]) and (last but not least), the third main principle, feedback.

Feedback is a fascinating and complex thing. We know that it’s one of the most important ways to improve performance, yet we also know from research that it can have negative effects on performance. Shank lists three roles that feedback plays, especially in relation to practice:

- Confirms understanding when correct.

- Corrects mistakes or misconceptions when understanding is incorrect.

- Closes the gap between what people can do and what they should be able to do.

These are all examples of corrective and directive feedback. The ones that are missing are called epistemic and suggestive feedback. This type of feedback includes suggestions and questions. For example, it includes questions such as “Why did you do it that way?” or “What other questions could you have asked?” (Guasch, Espasa, & Kirschner, 2013).

Shank explains how skill level and prior knowledge affect feedback. From all the learning solutions that I’ve seen in my life I have never seen a clear distinction between how feedback was delivered to novice versus more advanced learners (even when the solution offers a so-called ‘personalised learning experience’!). It’s these subtle nuances that make or break the effectiveness of a learning experience and Shank clearly shows the importance of these subtleties and how they impact the learner (in this case, the employee). Of course there are many other factors affecting feedback, such as how to give effective feedback, the receivers willingness and capability to receive the feedback, the type of feedback, and there might be more. As I said earlier, feedback is a complex thing!

Let’s move on to the actual strategies and tactics, including a bunch of good examples to make complex stuff easier to understand (and hopefully apply when you design learning experiences).

Practice and feedback strategies and tactics

The book includes 5 strategies and 26 tactics:

As usual, Shank bases all her recommendations on evidence (for this book it’s coming mostly from training research and apparently from Elvis Presley 😉). What I think makes this book a necessity for anyone who designs learning experiences is that Shanks explains hugely complex topics in an understandable way and the examples will help you to be able to apply the recommendations in your designs. I think this book (like the previous one – Write and Organize for Deeper Learning) should be on your desk and I guarantee you’ll use it as a guide to make good design decisions. The only thing that wasn’t convincing to me was the idea that peanut butter and bananas belong together. But I’m sure Shank will take that feedback on board.

References

Guash, T., Esposa, A., & Kirschner, P.A., (2013). E-feedback focused on students’ discussion to guide collaborative writing in online learning environments. Retrieved on 22 May 2016 on https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257221591_E-feedback_focused_on_students%27_discussion_to_guide_collaborative_writing_in_online_learningenvironments

Kalyuga, S. (2007). Expertise reversal effect and its implications for learner-tailored instruction. Educational Psychology Review, 19, 509–539.

Shank, P. (2017). Practice and feedback for deeper learning. Learning Peaks LLC.

[1] Note that this is a very complex topic. The way novices and experts learn is fundamentally different. This is also known as the expertise reversal effect (Kalyuga, 2007); meaning that what’s effective for novices is usually ineffective for experts. Learning design methods need to be adjusted based on level of expertise.

Reblogged this on kadir kozan.

LikeLike

M, thanks for this very thorough review of Patty’s book. I’ve always been a fan of her work! So logical! What I do continually have to wonder about though, is how you do what Patty is identifying as necessary for learning to occur, when all the companies and businesses want is faster training? There is so much focus by others on how to write smaller lessons, nuggets, mini this and that, etc, that you have to wonder how you put all this stuff Patty identifies into that corporate 5 pound bag of learning! Keep up the great work, both of you!

LikeLike