Everyone knows what I think about learning styles. Learning styles do not exist, and the myth that they exist is both ineradicable and toxic. A recent article goes further and looks at how ‘knowing’ that a student has a certain learning style affects the perception of what they can achieve in teachers, parents and the children themselves. In other words, when you hear that a child is a “visual” versus a “hands-on” (kinesthetic) learner, it changes your perception of that child’s abilities and intelligence.

What was studied?

The authors conducted three experiments. In the first, 73 children between 6 and 12 years old and 94 parents were introduced to two young pupils through what we call vignettes[1]. In the vignette, one young learner was described as a visual learner; someone who learns best when they can look at things with their own eyes. A second was described as a kinesthetic learner; someone who learns best by touching and feeling things with their hands.

Then, both the parents and the children were asked to rate both the intelligence and athletic ability of the two fictitious students. They were asked: “Is this student smart, a little smart or not very smart?” and also “Is this student sporty, a little sporty or not very sporty?”. What they found was that both the children and the parents rated the visual learner as smarter than the hands-on learner. However, there was no difference in terms of the rating for sportsmanship.

In the second experiment, the researchers studied 173 parents and teachers. Here they were also asked to choose which of the two fictitious students (visual versus hands-on) would be smarter or more sporty. They were, therefore, forced to choose between the two. Here, the parents rated the visual learner as more intelligent than the kinesthetic hands-on learner and the hands-on learner as more athletic. The same pattern was found for teachers.

An additional question was: “Do you believe that ‘individuals learn best when they receive information in their preferred learning style (e.g., visual, auditory, kinesthetic)?”; in other words, did they believe in learning styles. All parents and 85.1% of teachers believed in it!

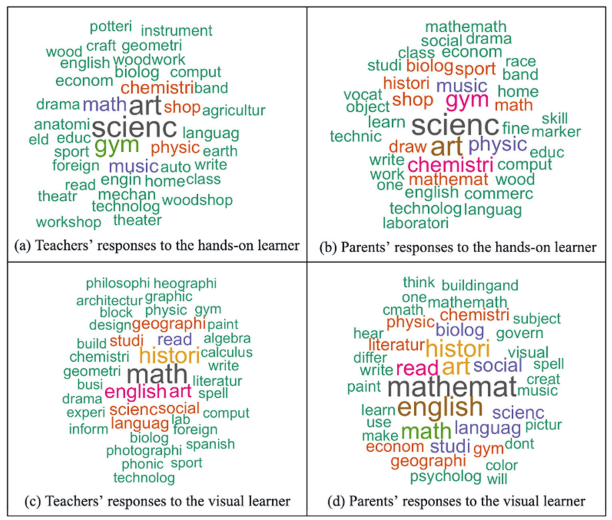

At the end, two open-ended questions were also asked inquiring as to which three school subjects students with each learning style would excel. For this exploratory open-ended question, the researchers created ‘word clouds’[2] that visualised the answers. Parents and teachers believed that students with different learning styles would have different strengths. They thought that visual learners would excel in math, history, English, art, and reading (in that order) and that practical learners would excel in science, art, physical education, and music (in that order).

In the third and final experiment, teachers and parents were asked to predict the grades that the two types of student would receive on their report cards for different core and non-core subjects. Here, parents and teachers alike thought that visual learners would get higher grades in core subjects like math, social studies, and language, while hands-on (kinesthetic) learners would get better grades in art, music, and physical education.

And what does that mean?

This research shows how biases about learning styles can affect perceptions of students’ abilities and intelligence. Parents, teachers, and children rated visual learners as more intelligent than hands-on learners. It’s striking to see that children estimate visual learners as being smarter even at a young age (6-12 years old!). In line with these biases, teachers and parents also predicted that visual learners would get higher grades than practical learners in most core subjects. In contrast, hands-on learners were seen as more proficient in non-core subjects, including physical education, music, and with smaller effects, art.

Together, these findings reveal a new consequence of the learning style myth, namely that thinking that a student has a particular learning style influences thinking about their academic potential and their abilities. This may mean that the expectations about these students are lower, that they do not receive the support to excel in certain subjects or even that they are not eligible for certain career opportunities (think of a vocational school advice instead of an academic high school).

Although this is the first study of its kind, it does add to the evidence that the learning style myth must be rejected if we are to embrace the many possibilities of our students.

Reference

Sun, X., Norton, O., & Nancekivell, S. E. (2023). Beware the myth: learning styles affect parents’, children’s, and teachers’ thinking about children’s academic potential. npj Science of Learning, 8(1), 46. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41539-023-00190-x.pdf

[1]Vignette studies present brief descriptions of people or situations (vignettes) to the participants of a study.

[2] A word cloud is a visual representation of the most commonly used words and/or phrases from answers to open-ended questions.

It might be easier to get a five-year-old to stop believing in Santa Claus than it is to get teachers to stop believing in learning styles. 😦

LikeLike

By “sporty” do you mean athletic? That’s completely different from sportsmanship, which has to do with respectful competition.

LikeLike

If I (or actually the researchers) meant sportsmanship, then I would have said that. You also could have looked at the actual article. It’s sporty.

LikeLike

You’re welcome

LikeLike

Teaching styles is probably a more important theme. “Preferences” may be better than “styles.” How would you describe a child who makes drawings of concepts, or another who has strength in auditory memory for concepts? The study above is simplistic in forcing choices. The idea of styles is more complex than these researchers appear to want the concept to be.

LikeLike